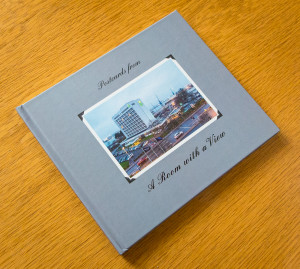

Over a number of years I have been photographing the view from the rooms of hotels where I have stayed. I’ve brought the results together in a photo book, Postcards from a Room with a View. The introduction to the book in reproduced below.

Over a number of years I have been photographing the view from the rooms of hotels where I have stayed. I’ve brought the results together in a photo book, Postcards from a Room with a View. The introduction to the book in reproduced below.

Inventing a Room with a View

The Signora had no business to do it,’ said Miss Bartlett, ‘no business at all. She promised us south rooms with a view, close together, instead of which here are north rooms, here are north rooms, looking into a courtyard, and a long way apart. Oh, Lucy!’….

‘I wanted so to see the Arno. The rooms the Signora promised us in her letter would have looked over the Arno. The Signora had no business to do it at all. Oh, it is a shame.’

‘Any nook does for me,’ Miss Bartlett continued: ‘but it does seem hard that you shouldn’t have a view.’

So begins E. M. Forster’s 1908 Room with a View and its penetrating study of conflicting values, classes and cultural perspectives, a study in which the ‘view’ is more than what is seen from a hotel room. While the desire that the Misses Bartlett and Honeychurch express for a room with a view now seems perfectly reasonable, it represents the coming together comparatively recently of a number of social, technological and economic factors.

The earliest windows were small, unglazed and served mainly to provide illumination and ventilation, or on occasions an aperture from with to shoot enemies. While the Romans were known to have used glass for windows, it was not until 17th century that glass became at all widely used in ordinary homes. Even so, windows were a taxable luxury and the glazing was almost always in small panes of crown glass which, while acceptable for letting in light, had very poor optical qualities for enjoying the outside world. It was not until 1848 with James Hartley’s invention of cast plate glass that it became common to install windows to create a room with a comfortable year-round view.

Any concern about the optical quality of earlier windows presupposes that people wanted to look at the view. Taking the cue from art, an appreciation of natural landscape and real townscape is comparatively recent in the broader sweep of history. Ancient Roman and Chinese art typically show grand panoramas of imaginary landscapes, usually backed by a range of spectacular mountains, waterfalls or maybe the sea. In western art landscape painting was seen generally as lowly in the hierarchy of genres. The technique for rendering perspective in landscape developed slowly and in the early 15th century landscape in art was shown, if at all, as the setting for human activity. Through into the 17th century landscape was routinely idealised, depicted as a pastoral idyll drawing on classical, mythological and religious themes. Portraits used stylised landscapes as backgrounds.

Any concern about the optical quality of earlier windows presupposes that people wanted to look at the view. Taking the cue from art, an appreciation of natural landscape and real townscape is comparatively recent in the broader sweep of history. Ancient Roman and Chinese art typically show grand panoramas of imaginary landscapes, usually backed by a range of spectacular mountains, waterfalls or maybe the sea. In western art landscape painting was seen generally as lowly in the hierarchy of genres. The technique for rendering perspective in landscape developed slowly and in the early 15th century landscape in art was shown, if at all, as the setting for human activity. Through into the 17th century landscape was routinely idealised, depicted as a pastoral idyll drawing on classical, mythological and religious themes. Portraits used stylised landscapes as backgrounds.

A significant shift towards an appreciation of landscape emerged in the shape of the Romantic Movement between around 1770 and 1850. The Movement accepted intense emotion – pleasurable awe, horror and apprehension – as a valid source of aesthetic experience, especially when encountered in confronting sublime, untamed nature and its picturesque qualities. Romanticism, as a reaction against the emerging industrial revolution, enshrined a strong belief in the importance of nature. The aesthetic appreciation of landscape was accompanied by the development of increasingly meticulous technique; and John Ruskin saw landscape painting as the ‘chief artistic creation of the nineteenth century’.

The appreciation of townscape, or cityscape, followed a similar evolutionary path. In the Middle Ages cityscapes appeared as backgrounds for portraits and Biblical stories. From the 16th through to the 18th century prints and etchings were made showing a bird’s eye view of towns and cities. Cityscape painting emerged as a separate genre in the Netherlands in the middle of the 17th century with Vermeer a leading exponent; and flourished in 18th century Venice, pre-eminently in the work of Canaletto. While the Romantic Movement may be seen as a reaction to urbanisation and the industrial revolution, 19th century art also depicted the emerging urban realities with a new aesthetic through the work of artists like Frith, Dore, Grimshaw and Maddox Brown. Indeed it is just such an urban foreground that Lucy Honeychurch enjoys eventually from her window:

The appreciation of townscape, or cityscape, followed a similar evolutionary path. In the Middle Ages cityscapes appeared as backgrounds for portraits and Biblical stories. From the 16th through to the 18th century prints and etchings were made showing a bird’s eye view of towns and cities. Cityscape painting emerged as a separate genre in the Netherlands in the middle of the 17th century with Vermeer a leading exponent; and flourished in 18th century Venice, pre-eminently in the work of Canaletto. While the Romantic Movement may be seen as a reaction to urbanisation and the industrial revolution, 19th century art also depicted the emerging urban realities with a new aesthetic through the work of artists like Frith, Dore, Grimshaw and Maddox Brown. Indeed it is just such an urban foreground that Lucy Honeychurch enjoys eventually from her window:

‘Over the river men were at work with spades and sieves….on the river underneath the window….its platforms were overflowing with Italians….Then soldiers appeared….and before them went little boys, turning somersaults….’

From the 1840s both landscape and townscape were the subjects for photography, the archetypal tourist activity.

But who was to appreciate the view? Early travellers, such as pilgrims and merchants, had other concerns; and appreciation of the view by those on the Grand Tour was limited to a privileged few. Enter Thomas Cook. In 1841, with an excursion from Leicester to Loughborough, Cook invented modern tourism and begat millions of travellers, who wanted a room with a view.

But who was to appreciate the view? Early travellers, such as pilgrims and merchants, had other concerns; and appreciation of the view by those on the Grand Tour was limited to a privileged few. Enter Thomas Cook. In 1841, with an excursion from Leicester to Loughborough, Cook invented modern tourism and begat millions of travellers, who wanted a room with a view.

With the rise of the industry came the demand for a new type of accommodation. Early travellers were put up in a variety of establishments, like inns, abbeys and caravanserais, where the orientation of the rooms was usually inward to a courtyard. Hotels in the modern sense began to emerge with the industrial revolution through the first half of the 19th century. These were often created through the conversion of existing buildings. Hotels were found in capital cities and historic towns, along coasts and by lakes. Services progressed through inside toilets, locks on doors and luggage lifts to private bathrooms, electricity and a la carte menus. Le Grand Hotel Paris, purpose designed by Alfred Armand, opened in 1862; and significantly the exterior facades, with high arched doors and Louis XIV widows, were designed to fit the surroundings of the Opera. In 1869 the Mena House Hotel was opened in an oasis of calm at the foot of the pyramids. The second half of the 19th century saw hotels located and designed to realise the potential of providing rooms with a view.

In effect, hotels in the second half of the 19th century became the embodiment of the technical, aesthetic and social changes that facilitated and valued the view as an object of the tourist gaze By the time of Forster’s characters’ visit to Florence their anticipation of a view of the Arno was no idiosyncratic whim, but a common and reasonable expectation.

The room with a view remains a selling point for hotels. Modest establishments, like the Red Lion in Cromer, promote it; Trip Advisor publishes ’10 hotels with incredible views’; and a construction hoarding in London has promised ‘Offices Panoramic Views New Hotel’. With the view comes premium prices – you can expect to pay 40-50% more for a room with a sea view at the Grand Hotel, Brighton.

The premium reflects supply and demand. Given the choice most guests will want a room with a view, but in many cases the geometry of the hotel or the location or both limit the number of rooms with the preferred aspect.

In practice many hotels today will be in places where the windows revert to their old function of providing illumination and the view may have little to commend it superficially, even with the benefit of good weather. So, in fact the experience for many ordinary travellers is not to have ‘a room with a view’ in Foster’s sense. They may be lucky enough to enjoy mountains and monuments, but in practice the Arno is more likely to be replaced by docks, car parks, service yards, back streets, motorways, railway lines, airports, construction sites and shabby neighbours. This is not, however, to be despised and dismissed: these quotidian views may reveal more about real places than the selectively picturesque ever can. And each is accompanied by its own soundscape, often the buzz of human activity replacing the silence of the mountains or the repetitive rhythm of the sea.

In practice many hotels today will be in places where the windows revert to their old function of providing illumination and the view may have little to commend it superficially, even with the benefit of good weather. So, in fact the experience for many ordinary travellers is not to have ‘a room with a view’ in Foster’s sense. They may be lucky enough to enjoy mountains and monuments, but in practice the Arno is more likely to be replaced by docks, car parks, service yards, back streets, motorways, railway lines, airports, construction sites and shabby neighbours. This is not, however, to be despised and dismissed: these quotidian views may reveal more about real places than the selectively picturesque ever can. And each is accompanied by its own soundscape, often the buzz of human activity replacing the silence of the mountains or the repetitive rhythm of the sea.

This album is dedicated not to those who enjoy great hotels with stunning panoramas, but to those who travel hopefully, experience everyday views of new places and take in the flow of daily life, as did Lucy Honeychurch in the end. It is a celebration of differences and the enjoyment of views beyond the conventionally picturesque. It follows in the line of photo books devoted celebrating crap towns and boring postcards.

Anyway, what’s in a view? Forster has George Emerson observe:

Anyway, what’s in a view? Forster has George Emerson observe:

‘My father’ – he looked up at her (and he was a little flushed) – ‘says that there is only one perfect view – the view of the sky straight over our heads, and that all these views on earth are but bungled copies of it.’