Following on from my post on 9th November, here are some edited highlights and my responses on issues raised by Module 2, which looked at photography a means of engagement with society

GM: I was glad to see that some work by my favourite photographer, Don McCullin, was included along with other images within what to me is the most worthy and important genre of photography, namely photojournalism.

BH: I share your view about photojournalism. I think it is the area where the medium achieves its maximum potential for expression and reaches levels that no other art form using the still image can match. This is photography’s unique achievement. Whether the images produced are works of art is a matter for debate, however. This is something we will explore in Module 4.

CA: Photojournalism is surely the most important sub-genre of the medium. Its enormous importance in campaigning cannot really be questioned. A Lewis Hine or Jacob Riis image would have had far greater impact than a written description, however powerful. This was recognised in the 1840s, when a couple of the Sub-Commissioners investigating women and children working in mines included sketches in their reports. These sketches were published – though inexpertly drawn, those images of women bent double in low tunnels dragging loaded wagons very much influenced public opinion, which persuaded a reluctant government that the law had to be changed.

BH: Yes, I agree about photojournalism and the importance of images in getting the story across, see above. I didn’t know about the sketches of women working, so special thanks for that – it provides more of the context in which to consider photography.

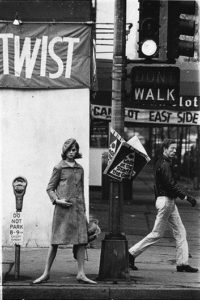

GM: Fashion photography holds no interest for me and is a sub-genre of studio and other posed portraiture which is similarly contrived. Fine if you want mugshots (or “likenesses” as the early photographers called them) but they completely lack the realism of spontaneous people images.

BH: I don’t share your jaundiced view of fashion photography. At its best it can be creative, stand as a document for a period of time (see Jean Shrimpton in New York, David Bailey, 1962) and reveal something of the preoccupations of our consumer driven society. I tried to look at some of this in the current module and will touch on it again in subsequent modules.

TB: Photography evidently has huge social power and influence, a power that is not readily understood or recognised. How this power is wielded and by whom is often not explored, but it is not neutral, nor is it necessarily benevolent.

BH: Yes, I agree about the power and the lack of understanding. Thinking back to comments on Module 1 about voyeurism and street photography, I recently wrote to Dave Runnacles, a Cambridge street Photographer: ‘I suppose one problem is that in the minds of some people documentary/street photography is conflated with the largely destructive work of the paparazzi. I believe that the value of photojournalism and street photography outweighs the objections to them. In an interview in Black+White Photography William Castellana defends the free use of street photography, referencing, “the rich photographic archive of street photography that currently resides in our museums, places we esteem and frequent to witness human achievement across all cultures.”’

TB: Photography as a technology has developed over a period of considerable social (and technological) change, enabling us to explore the intertwined relationships between the two. It is tempting to see photography as the passive respondent to society and its evolutions, whereas Module 2 shows that it is much more complex. Every photo is an intersection between a variety of factors, some of which come from the values and ideologies of the viewer, as much as those of the constructor or transmitter of the image. We tend to see the photo as passive and the viewer as active, whereas in many ways it is the other way round (cf the section on propaganda). Look, for example, at how we can construct our own identities via the images we “curate” (a very interesting word in this context) on our social media sites. Ironic, then, that so many selfies are taken by photographers with their backs to the wondrous backdrop which they wish to attach to their identity: photographer and subject beginning to overlap in interesting ways, as the personal becomes a form of public propaganda. Democratisation of image or assertion of power?

BH: I like the way you see the interaction between viewer and photograph as one that can be interactive and not passive and I agree with this. Sadly, the interaction is too often passive and thus there is limited understanding, see above. I deal with selfies and social media in Module 3. Your final point gets to the heart of one of the most important issues in this area: do we control social media, or does it control us?

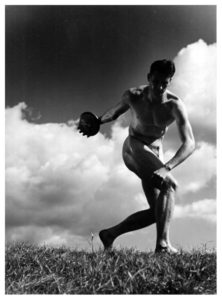

TB: The problems that we have with Leni Riefenstahl images is revealing (see The Discus Thrower, 1936), as we have to respond to ideologies we feel we should not approve of while at the same time responding to the power and the beauty of the image. The music of Richard Strauss presents the same problem. Keats would have us believe that Beauty and Truth are the same thing, a Romantic perception that still has power over us today. However, here it is evident through our discomfort that Beauty, though very powerful, is also amoral, a tool to be used in whatever way the propagandist wishes. We have less of a “problem” with this when beauty is used by Ansel Adams to propagandise in ways we approve. So is Beauty inherent in these subjects, or is it constructed by the photographer, or in the minds of the viewers? Do we even all agree about what is beautiful?

MM: Leni Riefenstahl: Her film of the 1934 Nazi Rally at Nuremburg, Triumph of the Will, as brilliantly accomplished as it is, is in retrospect, deeply disturbing. It was banned for many years after WW2. I remember seeing a striking later photo essay of her’s featuring the Dinka people, traditional cattle herders in the southern Sudan.

JS: The brilliant propagandist Leni Riefenstahl emphasizes the heroic qualities of the lionised Aryan figure.

BH: Very important points here. I’m about to start revising Module 4 on photography and art and this has prompted me to use it to reflect: whether beauty is an essential component of art; on the morality, amorality or immorality of beauty; and the distinction between the art and the artist. I don’t think Riefenstahl’s pictures of the Dinka people escape the criticism levelled at her work in 1930s Germany.

CA: Perhaps the image does need not be beautiful to be powerful – a snatched and even blurry image in a war situation ought to be more impactful than carefully-placed cannon-balls (Valley of the Shadow of Death, Roger Fenton, 1855), because it records what happened. But with time to act, and employing expertise, a shift of angle and emphasis concentrates the message.

BH: I’ve long felt that an image does not have to be technically perfect to have great impact; the skill of the photographer lies in being there, catching the moment and not worrying about f-stops, shutter speeds and hyperfocal distances. Robert Capa’s photographs of the D-Day landings epitomise this, see Normandy France, Omaha Beach, Robert Capa, 1944.

TB: We are predisposed to believe photographs because, usually for good reason, we tend to believe the evidence of our own eyes. It is also attractive to experience at a safe distance through a photograph those things we are not inclined to get too near to in real life or are simply unable to experience or inevitably absent at the critical moment. This was the pleasure of the popular photo journals in the past, and still is in National Geographic, etc. As for Fenton’s cannonballs, is this an early example of fake news, or is it a carefully constructed image that tells “the truth” more exactly than the scene that he originally found before him? Does authenticity matter? What will be the personal, social and political impact of deep fake imagery (usually moving image, I know, but it helps to focus thoughts on authenticity), where we are persuaded, by the evidence of our own eyes, to believe things that did not happen? All photos are, to an extent, inauthentic, given the tools available to the photographer to improve on nature (lighting, lenses, Photoshop, etc.), so is a deep fake image any different?

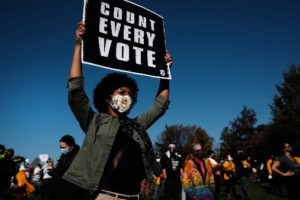

CA: Now it feels as if almost every image we see needs to be questioned. Not only is image manipulation itself easily achievable, but any image can be applied in misleading ways. I am thinking about Trump’s recent claims of election fraud, ‘supported’ by images which in the first instance of dissemination may be intentionally misleading – but are subsequently retweeted by those who honestly believe them to be genuine. Although we know manipulation can occur, we still trust a photographic image.

BH: It’s a sad truth that we do now have question so many images, certainly those taken in the modern era when manipulation is so easy. Module 5 will look at truth and veracity in photography, so these insights are helpful. Yes, we are inclined to believe what we see; we are also inclined to believe what we want to believe, that which conforms to our preconceptions (or prejudices), as propagandists have always known. I think the Fenton photograph is a good example of the need to understand the intention of the photographer (and how the picture is used): we must assume that he was trying to convey the horror of the fatal charge, not provide a truthful rendition of what the ‘valley of the shadow of death’ looked like afterwards. Yes, if people want to believe photographs, how much more will they want to believe moving deep fake images!

KB: I wonder what photos will come out of the coverage of the US election over the next 24 hours? In years to come the masks will date everything from 2020.

BH: Three election images are attached. Can we trust them? Are we seeing in them what we want to believe? Yes, street photography in 2020 will be easy to date – and have a short shelf-life for photojournalists. Assuming that we are excused wearing masks, eventually!