I’ve posted below the text of a short presentation that I gave to the U3AC Arts Forum yesterday to stimulate discussion around the subject of voyeurism.

I took a photograph of a couple cuddling in the seclusion of the Temple Lawn at Anglesey Abbey in October (see post 9th October 2022). J turned to me and said, ‘You’re a voyeur!’ I didn’t agree or disagree, but she had set me thinking about how much the arts (in a broad definition) are dependent on the gaze, on prying into private realms. (I’m excluding social media from this as it seems to be all about intrusion and self-exposure.)

What is a voyeur? According to Oxford Languages it is: ‘a person who gains sexual pleasure from watching others when they are naked or engaged in sexual activity’ or ‘a person who enjoys seeing the pain or distress of others.’ Well, I wasn’t being a voyeur in these terms, but the activity of getting pleasure from secretly watching other people’s private lives can reasonably be called voyeuristic. I would extend this to include enjoyment in the discomfort and ridicule of others.

Photography has history in this area. In On Photography, Susan Sontag sees the medium as intrusive and aggressive: ‘To photograph people is to violate them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.’ People may be made to look foolish or degraded. This is especially true of street photography in its various form, and never more so than in the work of the paparazzi, memorably introduced to us by the character of Paparazzo, the news photographer (played by Walter Santesso) in La Dulce Vita (Fellini 1960). The character was inspired by photojournalist Tazio Secchiaroli. In the succeeding decades we have routinely seen intrusion into the private lives of people, not just celebrities, and the print news media love it.

TV has a case to answer here too. At one level it’s about dwelling on the serious and sometimes gruesome aspects of news that we sit glued to watching as the cameras roll (despite, or because of the warnings that ‘there are some things that viewers may find upsetting’). There are the interviews where the interviewer remains silent, the camera zooms into close-up on the interviewees face, and their discomfort forces them to say something when they would probably prefer to keep quiet. Then there are interviews got under false pretences for the gratification of public prurience.

That enjoyment of discomfort and ridicule also finds a home in mainstream entertainment, such as ‘Strictly Come Dancing’ – we laugh at the hapless performers while wondering why they do it (for the money and for moments of fame, of course). Programmes like ‘Love Island’ are more directly voyeurism, with their ‘Will they?’ ‘Won’t they?’ leering at the narcissistic couples.

It’s not just the work of the mainstream popular arts and media.

Take painting. Tracey Emin invites us into her sexual and medical private lives. Lucien Freud opened up the human body to all who care to look – and many of us do.

It’s common theme in film, like Rear Window (Alfred Hitchcock 1954), though not often as true to the extremes of voyeurism as in Peeping Tom (Michael Powell 1960). On stage, Look Back in Anger lays bare the struggles in the married life of Jimmy and Alison Porter

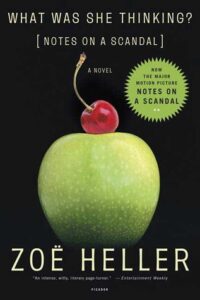

In literary fiction there is misery to enjoy in Dickens; and plenty of voyeurism in modern novels, such as The Collector (John Fowles 1963), Felicia’s Journey (William Trevor 1994) and Notes on a Scandal (Zoë Heller 2003). In non- fiction Angela’s Ashes (Frank McCourt 1996) dwells on (and probably exaggerates) the misery of a Limerick childhood while Annie Ernaux lays out the agony and ecstasy of an affair in Getting Lost (2022).

So, some questions.

Are we all voyeurs behind the fig leaf of the arts now?

Is there a public interest justification?

Do ‘celebs’ deserve it?

Is it voyeurism if the subject is complicit in it?

Four key points emerged from the discussion, for me.

- Voyeurism is a greyer area than the simple definitions would suggest.

- Any consideration of voyeurism has to take into account the viewer, the subject and any intermediary, e.g. photographer, interviewer etc.

- It depends on the context and purpose – there can be a public interest justification.

- We are fascinated by other people, their lives and their behaviour and the gaze in acceptable where: there is consent; there is no exploitation; and not one is harmed