The Dickens Boy (Thomas Keneally, 2020) fictionalises the true story of the early years of Edward Dickens (known as Plorn), Charles Dickens’ youngest son, in Australia. It is set largely on the remote sheep station at Momba, Wilcannia, New South Wales and chronicles roughly the years 1868-70. Momba is run by brothers Edward and Frederic Bonney.

Soon after Plorn’s arrival at Momba, Frederic Bonney reveals his interest in the local Aboriginal people. ‘The natives are in any case a study of mine. These people along the river are named Paakantji. … I could say I’m and enthusiast for the Paakantji.’ An aspect of his interest is then revealed:

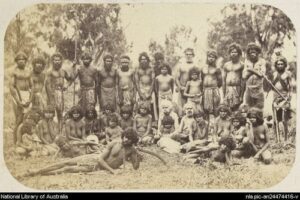

‘Indeed Fred takes wet plate photographs of them,’ said Edward, as if he were uncomfortable with the brother’s previously stated enthusiasm.

‘That must be very difficult, Mr Bonney, ‘I [Plorn] interjected.

‘It’s true that setting up the Colloidal plate takes some practice,’ said Frederic. ‘But none of them are shy of the photographic apparatus itself. I’ve heard tales of Africans and red Indians being flighty about the camera, but not the Paakantji.’

‘It’s because they trust you,’ said Edward as a compliment.

‘And when I ask them to be still, they are stiller than the grave, for however long – forty seconds perhaps, while the device captures their image. It’s true, I hope that they expect no malice from my brother and me.’

A few days later Bonney asks Plorn if he would like to visit the Paakantji camp and help him with his photographic equipment. He explains that he makes his own plates and says: ‘It gives me great satisfaction. They say in America they have ready-made dry plates, but one feels closer to whatever image ends up on them if you make them yourself.’ He shows Plorn the process of coating the plates with collodion, followed by immersion in a silver nitrate bath, and explains that the plate has to be made just before it is exposed, ‘If you let the plate sit too long it won’t achieve the effect’. In response to a question from Plorn, Bonney says that he learned it all ‘from manuals and trial and error… [and] a travelling photographer from Sydney.’

With the plate loaded they go to the camp where Bonney arranges the people. Plorn notes, ’He was a serious practitioner, who could not have taken greater trouble with a set of important Londoners.’ Frederic makes a number of ‘darts into and out of the dark cloth to adjust the lens and check how things looked, asks the Paakantji of they are ready and removes the lens cap. ‘[T]he subjects all stood still, those unbreathing antique faces. It was as if even the desert oaks behind the native huts seemed to hold their breath, waiting out the necessary time for the light of the day to inscribe their images on Fred’s glass plate.’

That evening Frederic shows Plorn ‘a thick cardboard print taken that morning’. ‘The light is good and the images sharp,’ he told me. ‘I’ve written the names on the back so that it can be an aide memoire for the people depicted.’

Later in the story the residents of Momba are taken hostage by bushrangers lead by Dr Pearson.

‘Is there anywhere we can confer, Mr Bonney?’ asked Dr Pearson.

‘Yes,‘ said Fred, resolute. ‘We can use my office by the kitchen.’

He led the way to the back of the house and into his office with his pictures of Paakantji on the wall. On entering, the two bushrangers were taken by the magic and science of this.

‘How do you get these, Mr Bonney?’ Pearson asked.

‘It is just the impact of light on certain chemicals coated on a glass plate. Surely you’ve seen photographs before.’

‘It’s not your work, is it?’

‘Yes. I am a photographer. But it is only science. The science of light.’

‘It is more than that,’ insisted Pearson.

In the darkest episode of the story Dickens witnesses the results of a massacre of 24 Aborigines belonging to the Barakoon group. He sends a message to Frederic, who comes to take photographs. ‘One of the men accompanied him to the site of the massacre, where he took a photographic tour of the graves, opening three of them to make plates of the remains. He told me he intended to publish them to provide visibility to the slaughtered.’ This is not recorded historically as a specific event, but stands for one of several massacres in the 1860s.

The novel is based on the experiences of a real person, Dickens. Frederic Bonney is equally real and it’s worth quoting at length from his Wikipedia entry.

[Frederic] Bonney’s occupation was as a grazier but his hobby was photography and anthropology. He took many pictures of the Paakantyi people who had traditionally lived along the Paroo River. These people had been devastated by disease and the invasion by foreign immigrants. … Bonney’s attitude to these people was not as judgmental as many and he took natural pictures which recorded their lives. … [His] pictures have been published recently and in his time they were exhibited at the Melbourne Exhibition in 1880. Bonney’s pictures of Wonko Mary record a mourning tradition – Wonko Mary is shown with a ‘widow’s cap’ which she has made from gypsum (kopi) and water, and has moulded to her head.

Frederic sold Momba station and he returned to Staffordshire in 1881. He travelled back the long way and he visited Hawaii where he again took photographs during a month there.

Bonney recorded some important images through his enthusiasm for photography. Some of his original images have been lost, but his work has been published in two books and they include photographs of the Paakantyi people. Unusually for his time, he wrote the people’s names on the back of his photographs, and these can be cross-referenced to his notebooks. This information can reveal connections to Paakantyi families living today.

Bonney’s Australian photographs are held in the State Library of NSW (Mitchell Library) and the Australian National Library.

A book, People of the Paroo, by Jeannette Hope and Robert Lindsay, has been published, containing all Bonney’s surviving Australian pictures. Some of these have only recently been identified.

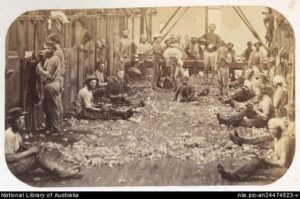

Keneally’s integration of Bonney’s photography into the story of the young Dickens is authentic and reflects the practice of photography at the time. The collodion wet plate process (widespread from c.1854 to the mid-1870s) was complex and use in the field required a mobile darkroom. This is reflected at a point in the story when Frederic is persuaded not to take his ‘camera apparatus’ to a distant cricket match so the party can travel in a ‘light sulky’. However, the reference to dry plates requires some elaboration. Experiments with dry plates had been made from the 1850s, but these had been unsuccessful until Richard Maddox developed an effective process in 1871. Bonney may have heard of the experiments in the late 1860s, but they were not available as an option at the time in which the story is set. A further complication arises from the dating of the surviving photographs which is usually given as the 1870s, when dry plates may have been available to Bonney. His insistence that photography is only a science reflects early attitudes to the medium and predates the foundation of the Linked Ring in 1892.