The Photographer’s Wife (Robert Sole, 1996) is set in the world of late 19th century Egypt. Three things drive the narrative: the relationship between the photographer and his wife; her emergence as an increasingly creative photographer; and the colonial wrangling between England and France over the control of Egypt at the time of the Mahdist uprising.

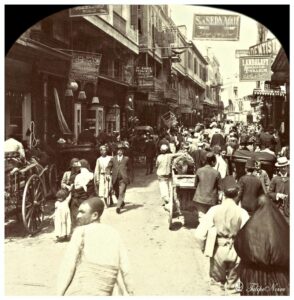

Milo Touta is a small-time photographer with a studio in Cairo; he scrapes a living doing portraiture, group photographs and summer stints as a beach photographer, but draws the line at postcards of the sphinx and the pyramids (occasional commissions for more risqué subjects are another matter). He’s dashing, a gifted story teller and ambitious. And unromantic about photography. ‘”A good photographer’s secret”, he used to say, “is ten per cent technique, ten per cent artistic sense, and eighty per cent commercial flair.”’

Milo meets Dora Sawaya when she is painting on the on the beach near Alexandria and they spa verbally over the status of photography as an art form. Differences put aside, they marry and Dora is drawn into Milo’s business. Not content to stay quietly at home, she persuades him to teach her photography. We are introduced to a world of cumbersome studio and ‘field’ cameras, head clamps, props (‘bric a brac’) and painted back drops, liberal retouching and hand colouring (to which Dora brings a rare skill and sensitivity) . Photographic plates are developed in smelly baths, including now vanishingly rare treatments with alum and hydrosulphite – it’s the dark room as laboratory. (Much later Milo reminisces about mercury vapour and ether, which appears anachronistic: he would be unlikely to use either the Daguerreotype of the collodion processes in the 1890s.)

In their world photography is revealed as stressful, something to get dressed up for and an ordeal to be faced, including the fear of moving and spoiling the shot. The resulting photographs are treated with reverence as precious objects.

But it’s not a static photographic world of plate camears. Milo acquires a Kodak camera in the 1890s, presumably a Kodak 1 (introduced in 1888). The camera is sent off and the prints returned. Dora declares that, ‘”It isn’t very practical.”’ Emile is confident that ‘”The button pushers … present no threat to professionals like us.”’ Dora later considers buying her daughter a ‘Photo-Éclair’ ‘such as practical jokers conceal beneath their waistcoats’ (this probably refers to the Stirn camera introduced in the 1880s). Emile later acquires a roll film camera hidden in a walking stick.

Dora’s skill as a photographer soon surpasses that of her husband and her talent brings financial success to the studio. She reads and follows advice in L’Amateur Photographer and tries landscapes of the sphinx and pyramids. She has the studio and darkroom rebuilt; and she imports a photometer to measure exposures and an enlarger. She experiments with lighting and poses and confides in her notebook, ‘I don’t try to beautify faces … I try to strip off their masks – to lay them bare, as it were.’ And she reflects: ‘My plaster Apollo, lit with care in front of a plain backcloth, looked far more animated than one of my husband’s customers stiffly posed in front of a raging sea.’ Dora aims for spontaneity in her photographs: a portrait of her friend Sief wins first prize at the Salon de Photographie in Paris. She juggles photography and childcare.

She also has a deepening friendship with a British army officer, William Elliot. He writes from the Sudan in 1897 about photographers based at the headquarters there, who have ‘a wagon fitted out as a darkroom’ and a camera that ‘can be loaded on a pack horse or mule, complete with plates and lenses, when the terrain is too rough for the wagon’.

At a social gathering editor of the Semaphore d’Alexandrie, asks her opinion of the few photographs that appear in his newspaper. She’s not impressed. ‘” Many of them are useless,” she said bluntly, “The text conveys more than the pictures that accompany it, which are very dull.”’ Taking note of the criticism, the editor subsequently approaches Dora with a proposal to publish a ‘photographic report on the reconquest of the Sudan’. Dora demurs saying she is too busy.

But her relationship with Emile worsens and she leaves him. It’s the catalyst for her to approach the editor and declare, ‘”I’m ready to go to the Sudan.”’ He gives her an open brief, saying that: he will expect more than just portraits; and she will be credited and be free to market her photographs once the paper has published them. She sets off with a ‘field camera, and a bag crammed with photographic equipment’.

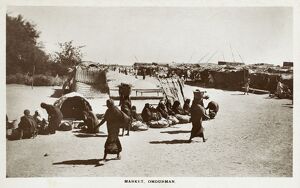

At Khartoum she meets Elliot, who shows her round. He takes her to Omdurman, where she says she does not want to visit Kerreri, the site of the battle, instead she wants to go to the market ‘to meet some living people’. She spends every morning in the market and says, ‘”I’m just looking … I’m trying to take it all in.”’ William, surprised says, ‘”but you see the same thing every day.”’ ‘”…not necessarily with the same eyes”’, she replies.

Two weeks after her arrival she goes on a day long tour of Omdurman, taking her camera for the first time. ‘She knew exactly what she wanted to photograph, as if she has already picked out the locations, assembled her subjects, and studied their mannerisms. No sooner were they in front of her lens than she tripped the shutter without giving them any precise instructions. She used only a dozen sensitive plates…’ Dora’s interest now is in unposed pictures of people in the villages, not of formal portraits of the great and the good in Cairo.

A photograph by Dora, ‘Sudanese women near Omdurman’, appears on the front page of Semaphore d’Alexandrie. ‘Dora’s photograph shows six bare-breasted women facing the camera. Five of them had pitchers on their heads … Every face seems expressive of boundless melancholy – more reminiscent of a millennially wretched existence than a hundred newspaper articles.’

It is not only Dora’s skill that changes over time, so does her attitude to photography as a creative medium. In an early meeting with Emile she is anti-photography and argues, ‘”An ordinary paintbrush can do more than all your mechanical and chemical processes put together.”’ A little later, when Emile praises the reproducibility of photographs, she retorts, ‘”I prefer my easel. Besides, one painting by a master is worth, more than two thousand photographic prints.”’ But working with Milo and frustrated with the results of her efforts at painting, she ponders, ‘I was beginning to wonder if the medium of expression I had vainly sought in painting would be granted me by photography.’ Soon she is explaining to a friend, ‘”Photography doesn’t just record the world. … It beautifies and elucidates it, so to speak.”’ She has continually to remind herself that painting and photography are two different things; and comes to believe that photographers “‘don’t show you only what they’ve seen, but how they’ve seen it.”’ She writes in her notebook: ‘Photographs are not just imprints of a place; they’re imprints of time as well. By capturing the moment with a camera and recording it on paper, they eternalize it.’ She thinks her most successful pictures are ‘almost self-portraits’.

Dora’s attitudes towards photography reflect the 19th century struggles for it to be taken seriously as an art form trying to find its own voice. With her formal, pictorial view of the world she would probably have felt at home with ideas emerging then through the Linked Ring and the Photo Secession.

Dora emerges as an accomplished professional ahead of the general condition of women at that time. But historically she would neither the first nor unique in the realms of photography. Lady Hawarden and Julia Margaret Cameron precede her; Frances Benjamin Johnson wrote ‘What a Woman can do with a Camera’ in 1897. Dora’s story as a studio photographer is by no means impossible, but to achieve what she does in North Africa at that time is would be remarkable.

Her exploits in the Sudan take her out of the comfort of the studio, the suitable realm for a women of her time, and appear even more remarkable. Though there are precedents in the work of travellers and photographers such as Isabella Bird (1831-1904), Gertrude Kasebier (1852-1934) and Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864-1952), this aspect of the story seems less credible. To be commissioned by an editor and given by-lines and rights to the photographs seems anachronistic and anticipates a form and practice of photo journalism that didn’t really emerge until the 1930s. What does have the air of authenticity is the publication of the photograph of ‘six bare-breasted’ women. This is consistent with photography as a tool of imperialism showing indigenous people as exotic and uncivilized, photography that is both racist and sexist (see post 9th March 2022).

The Photographer’s Wife tells an engaging tale in which photography has a major role. It paints a fairly convincing picture of the practice of photography in the 1890s, but it’s not a contemporary record. How would photography look in a novel written then?