I thought I knew all about the origins of the Cambridge Darkroom. But I didn’t know how much depended on a tour of British photo galleries in a rusty Renault 4 van with a packet of biscuits and a flask of whiskey. This investigation of good (and bad) practice was key to the evolution of the St Matthew’s Photo Workshop into the Cambridge Darkroom, according to Pavel Buchler.

Pavel gave this anecdote at the Radical Art in Cambridge round table event held on 26th October. The aim was to explore innovative exhibitions, artists’ residencies, publishing and community photography in Cambridge in the 1980s. Speakers included Pavel Buchler (Co-director Cambridge Darkroom 1984-86), Mark Lumley (Co-director Cambridge Darkroom 1982-90), Dr Sharon Kivland (artist) and Simon Cutts (founder of Oracle Press). The event focused on the work of the Darkroom, perhaps inevitably given the composition of the panel, though the context set by parallel work at Kettle’s Yard, artists’ residencies at King’s College and the support for women artist at New Hall (now Murray Edwards College) was acknowledged.

I outlined some of the background to the founding of the Cambridge Darkroom on my blog on 15th August 2022, which directed readers to the detailed history on Roy Hammans’ Golden Fleece web site. Mark and Pavel described this early history and explained how a meeting with Barry Lane, then the Art’s Council’s Photography Officer, gave focus to the need to establish a permanent gallery if the momentum achieved by the Photo Workshop and nascent Darkroom was to lead to something of wider significance. Hence, Mark and Pavel setting out in the Renault to learn how others did it – and coming back with the intention to do it better.

Roy’s work in bringing together material on his web-site and the articles in creative camera 10/1989 have done much to put the history of the Darkroom in the public realm. This event was valuable in giving an opportunity to review the story in a longer-term perspective and present it to a new audience. My notes here focus on the Darkroom (which is not to diminish the importance of the other players, who will find their own voices). Was the Darkroom radical? Five facets of the answer to that question emerged through discussion.

First, there is the unexpected nature of its very success in a City that might reasonably have been seen at the time as an artistic backwater, a place starved of artistic infrastructure, Kettle’s Yard, the Fitzwilliam Museum and a good foundation course at the Cambridge College of Arts and Technology notwithstanding. The success was founded on: the community roots from which the organisation emerged – it was internally, not externally driven; and the energy and vision of the founding members and directors.

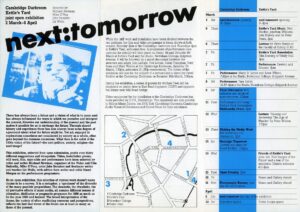

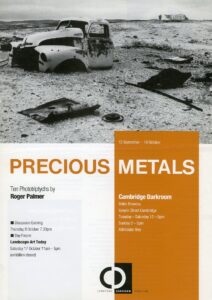

Second, the decision not to restrict the gallery to showing work in one genre (many galleries focused on social documentary work at the time), but to include anything that was considered of high quality. This meant recognising artists using photography, not just ‘photographers’, the sort of work that few other people were was showing, work relegated to the corridor and the staircase. The Darkroom was open to new thinking and marginalised artists moved into the gallery as boundaries were broken down. An atmosphere of mutual trust was established between practitioners and the gallery; and artists like Craigie Horsfield, Roger Palmer and Mona Hatoum were introduced to a wider world. This can be said to have achieved its fullest expression during the life of the Darkroom with the two open shows curated jointly with Kettle’ Yard, next:tomorrow (1986) and Death (1988).

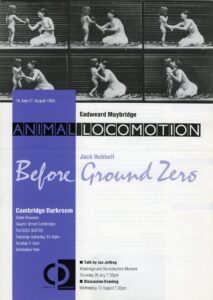

Third, the programming. This was conducted at a hectic pace, e.g. 12 show in 1984, 13 in 1986 and 1989. This not only maintained interest in the gallery, but through group shows helped to build a community of artists (however they may wish to self-identify) working with photography. This dynamic was reinforced by using the flexible gallery space creatively so that work was shown coherently and to maximum effect. A community darkroom and workshops continued to operate in parallel with the gallery.

Fourth, the strong identity established by Pavel Buchler’s designs for the Darkroom’s publicity material and publications. It was eye-catching, instantly identifiable and contributed crucially to projecting the organisation’s professional credibility.

Fifth, the credibility across all areas was used to exert leverage on funding bodies, aided by champions who bought into the vision – Barry Lane at the Arts Council, Jane Heath at Eastern Arts and Liz Gard at Cambridge City Council. Trust was established between these bodies and the Darkroom (mirroring the trust between artist and the Gallery directors).

The Darkroom was a major contributor to radical art in Cambridge. It provided access for people without power. At one level for artists who were leading precarious lives without dealers and access to other galleries – the Darkroom gave them a way of doing things differently. At another level, access for the Cambridge community, which was offered the opportunity to engage with new and challenging art. It influenced the cultural landscape nationally and locally through an integrated approach to both the art itself and the way in which the gallery was run.