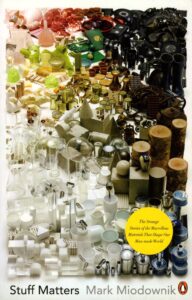

We routinely take for granted the materiality of the world around us: we don’t bother to think about why cutlery doesn’t rust, how concrete buildings stand up or why chocolate tastes good. We don’t ask what goes on in the structure of materials that allows them to behave in the way they do. In Stuff Matters (2014), materials scientist Mark Miodownik explores everyday objects as miracles of chemistry, craft, design, engineering and ingenuity. In dealing with glass, plastics and paper, he touches of the world of photography.

Glass is durable and transparent. One of its properties is that when light strikes the surface at an angle it is refracted, it is this that makes an optical lens possible, with the curvature of the glass resulting in a different angle of refraction. ‘Controlling the curvature of the glass means we can magnify images, which allows us to make telescopes and microscopes.’ Miodownik might have added camera lenses.

The invention of celluloid in the 1850s, and the development of the manufacturing process in the 1860s by John Wesley Hyatt in the USA, made available a light, flexible material as the base for photographic film, replacing expensive, heavy, and fragile glass plates. Exploited by George Eastman it was as central to the photographic revolution in the 1880s and 90s as his invention of portable, easy to use Kodak cameras. The availability of flexible roll film eventually gave birth to the motion picture industry. (Eastman was not the first to exploit these properties of celluloid: John Carbutt had invented celluloid plates a decade earlier.)

Materially, the traditional photograph is only a more or less dense layer of silver crystals embedded in a gel on a firm paper support. Yet Miodownik says ‘ it is hard to overestimate the effect of photographic paper on human culture’; in a passport a Photograph ‘has been accepted as the final arbiter of what we look like and, by extension, who we actually are’; and the means of capturing the image means that ‘the image itself is seen as impartial’. He also argues that a printed photograph in a newspaper makes the event it shows more real than any other form of news reporting. A photograph is ‘a material fact of history that contributes to our collective memory.’

Miodownik concludes by looking into things at the micro, nano and atomic scales, where new technologies are shaping the world of ‘stuff’. They have already done so in photography: microchips ‘surround us – they play our music, they take our holiday photos’. But sometimes things rise above the latest functionality. He argues that materials ‘mean something, they embody our ideals, they give us part of our identity … and in every aspect of our lives we choose materials that reflect our values.’ In that we can see the resurgence of vinyl records and the continuing appeal of analogue photography. For me a ‘real’ photographic print will always be better than a picture on a screen. Film and paper offer a sensuous experience that the digital world cannot match.